Dog Cloning For Special Forces: Breed All You Can Breed

Decision analysis of whether cloning the most elite Special Forces dogs is a profitable improvement over standard selection procedures. Unless training is extremely cheap or heritability is extremely low, dog cloning is hypothetically profitable.

Cloning is widely used in animal & plant breeding despite steep costs due to its advantages; more unusual recent applications include creating entire polo horse teams and reported trials of cloning in elite police/Special Forces war dogs. Given the cost of dog cloning, however, can this ever make more sense than standard screening methods for selecting from working dog breeds, or would the increase in successful dog training be too low under all reasonable models to turn a profit?

I model the question as one of expected cost per dog with the trait of successfully passing training, success in training being a dichotomous liability threshold with a polygenic genetic architecture; given the extreme level of selection possible in selecting the best among already-elite Special Forces dogs and a range of heritabilities, this predicts clones’ success probabilities. To approximate the relevant parameters, I look at some reported training costs and success rates for regular dog candidates, broad dog heritabilities, and the few current dog cloning case studies reported in the media.

Since none of the relevant parameters are known with confidence, I run the cost-benefit equation for many hypothetical scenarios, and find that in a large fraction of them covering most plausible values, dog cloning would improve training yields enough to be profitable (in addition to its other advantages).

As further illustration of the use-case of screening for an extreme outcome based on a partial predictor, I consider the question of whether height PGSes could be used to screen the US population for people of NBA height, which turns out to be reasonably doable with current & future PGSes.

Military and police dogs are specially trained for their jobs. Only some dogs are up to the task, but like training seeing-eye guide dogs, it’s difficult to know in advance and many dogs will wash out of training as expensive failures, with even fewer being able to handle the extreme life of a Special Forces dog; then they may get injured on the job, develop hip dysplasia or cancer, cutting short their career, and leading to perennial shortages. This is despite the best efforts of the (mostly European) breeders who raise the Malinois, German Shepherd, Belgian Shepherd, and Labradors preferred for war dogs.

The 7 Tomorrow Dogs/Toppies cloned in 200718ya.

In 201411ya, Bloomberg reported on an interesting aspect of Sooam Biotech, the famous South Korean dog cloning company: they were cloning a Special Forces dog. If it’s hard to be a K9, it’s even harder to be a SF dog, able to jump out of airplanes (they have special parachute harnesses), go on raids, carry cameras with them, even (reportedly) wear little doggie hoods with infrared camera goggles for night work; so valuable and specialized are such dogs that special $26,547.03$20,0002017 animatronic dog models like the “K9 Hero-Trauma” are sold to train medics how to treat injuries like gunshot wounds or amputations. If you have a successful SF dog… maybe the clone will be much more likely to succeed than a random puppy picked from one of the usual breeders, and you can make as many clones as necessary long after the original has gone to Dog Heaven.

Clones of elite individuals are increasingly common in agriculture; plants, like the myriads of apple varieties, have always been propagated clonally, but cloning of cattle has made major commercial inroads1—not just cloning of cattle for beef or cows for milk, but also clones of rodeo bulls (the logical extension of the highly successful selective breeding for rodeo bulls). A striking example of this approach is the world polo champion Adolfo Cambiaso, who is so enthusiastic about the benefits of horse cloning that he has cloned his prized polo horse not once but >10 times, and has rode entire teams of clones to repeated victory. On the other hand, dog clones are still extremely expensive (~$129,371.51$100,0002018) and prices have not yet come down to the ~$12,937.15$10,0002018–$25,874.3$20,0002018 of cattle.

There may be cheaper alternatives to improving SF dog yield: training is probably well-refined and can’t be watered down without risking lives, but that leaves a place for improvement of what is trained, the selection into training—better prediction of SF potential means fewer dogs washing out means less total money spent to produce a successful SF dog. The predictions don’t work well, but the descriptions of screening suggest there’s a lot of room for improvement: the research literature supports the generalization that dog and cat behavioral measurements are not all that predictive. They may be badly designed or testing the wrong things, or there may be inherent noise which can be fixed by doing multiple measurements. (Even something as apparently mechanical as offering catnip to a cat can have different results from occasion to occasion and may have rater-specific effects, perhaps because—“set and setting”—the cat is fearful and distrusts the person offering the catnip that day, with the anxiety shutting down any response or play.) Many described measurements in the literature measure a dog once, on one day, by one person, for example, measuring aggressiveness by taking away food and seeing if the dog snaps at the person, and that’s the whole test. Such a test will be hindered by day-to-day variation (perhaps he is stressed that day), different levels of liking for that particular food, disliking of the person taking the food, sheer randomness in the particular split-second decision of whether the dog decides to express their aggression—likely would be much stabler and predictive if they were done multiple times in multiple ways by multiple people etc (although such extended testing would increase the cost of testing). Of course, that would take more time and would cost a lot more, and it’s unclear the increase in predictions is worth it.

However, ranking for selection is easier than prediction of all datapoints: only the ordering matters, and only the ordering in a particular region (near the threshold) matters. When considered in a real-world context, such predictive improvements do not need to be all that large (a point long made by psychometricians & industrial psychologists eg. 1939/ et al 1979/1996); counterintuitively, a score or test which correlates, say, r = 0.10 with an outcome, which in many areas of science would be dismissed as a trivial correlation of no interest, can be quite useful in screening & should not be dismissed as ‘small’—and the rarer the outcome, the larger the benefit.2 In the case of dog cloning, our ‘score’ is the extent to which a donor’s performance predicts the performance of its clones, through their shared genes.

Both approaches could wind up being expensive and there’s no a priori answer about which one would be more cost-effective. To a certain extent, they are also mutually exclusive approaches: dog cloning is so expensive that unless it results in high probability of success, it probably won’t be cost-effective at all, and if the probability is sufficiently high, then testing is no longer useful (because you would save money by simply trying to train all clones), so better testing is unlikely to then pay for itself. Testing to gain information is only profitable in a certain intermediate region of probabilities & costs/benefits.

So it’s not absurd to think that dog cloning could work out well for training SF dogs, and I took a closer look.

Benefits

The benefits of dog cloning are not limited purely to replicating an elite SF dog. The potential benefits of dog clones include:

-

lower total cost: the primary reason for cloning is that since dog clones are more likely to succeed in training given any reasonable heritability, they may reduce washout costs enough to compensate for the expense of cloning.

But the total lifetime cost of a dog goes beyond success or failure in becoming a useful dog. Successful dogs can still learn at different rates, and require more or less intensive intervention by trainers. Dogs can learn multiple roles, so a ‘success’ may only be a partial success, like a dog who is approved for odor detection of bombs or drugs, but can’t be used on patrol or raids. They can have longer or shorter careers, reflecting levels of competence and medical issues (hip dysplasia constantly comes up in war dog discussions as a disabling medical problem, and is highly heritable).

Hence, discussing only success/failure in training and the reduction in average training cost will seriously underestimate the benefits of cloning the best: clones of the best SF dogs will train faster, with less effort/time, excel at more roles (more likely to be acceptable for at least one role), be less likely to have crippling medical issues that kill them or end their careers prematurely, and have longer careers in general.

-

greater scalability in dogs: there are only a few dog breeders, and they have only a relative handful of bitches at any time

Even if demand spiked in a war and 1,000 more dogs were needed yesterday, they wouldn’t exist—dogs take a certain amount of time to reach sexual maturity, have only so big litters, mating in inbred/narrow pedigrees like German Shepherds/Malinois must be managed carefully to avoid exacerbating existing genetic issues (and eating the seed corn), training takes a while (Ritland notes that the US Navy takes delivery of 2-year-old dog candidates), and so on. In reading about US war dogs, a perennial theme noted by 2005 is that a war happens (WWII, Vietnam, War on Terror), war dogs become incredibly useful to frontline troops, and dog supply simply cannot keep up.

Use of cloning can break part of the bottleneck by enabling surrogacy in female dogs of other breeds which are not scarce, and by enabling unlimited reproduction of a particular dog. (This doesn’t require cloning, since one could create the necessary embryos with standard IVF, but since the IVF/surrogacy is necessary, why not use cloning as well?)

This option is highly valuable and justifies dog cloning on its own; and because this option is available, militaries can more steeply reduce war dog numbers during peacetime as no ‘reserve’ is necessary.3

-

greater scalability in facilities: another bottleneck might be not the number of dogs, but the infrastructure for housing/training/testing the dogs.

There might be only so many dog kennels and experienced dog trainers at any point, and increasing the number could take a while. (You probably want the trainers and program management to have SF dog handler experience themselves, but it might take decades for a recruit to become an experienced trainer.) So given the inelastic throughput, here it would be valuable to improve the quality of inputs, which will increase the total yield, simply because it means less dilution or waste of scarce fixed housing/training/testing slots on dogs less likely to succeed.

-

greater predictability:

-

Response to Training: yield might be increased simply by the inherent homogeneity of clones allowing improved training by greater experience, rather than any increased genetic merit.

One of the reasons Adolfo Cambiaso gives for investing so heavily in clones of a single polo horse is that he has learned from his long experience with the donor horse how best to train them: each new clone can be given personalized training which he knows it’ll respond best to, because he’s trained many clones before them. If there is some consistent weakness the clones are prone to, he can start addressing it before it even shows up. He also has gained long experience with their injury propensities, preferences, and other behavior, instead of starting from scratch with each new colt. Their similarity avoids the need for learning or wasted pedagogy.

Dogs presumably vary as much as horses do, and training of clones could benefit from this sort of homogeneity. (Since dog trainers will have never encountered clones before, and identical twin dogs are vanishingly rare, there’s no way to know how useful this would be in practice until large numbers of dog clones have been trained by individual trainers.)

-

Reduced Variance for Experimentation or Analysis: statistical power scales poorly with increasing variance; relatively small increases in noise can require much larger n to overcome. The most efficient experiments are within-subject experiments, which avoid comparisons between individuals, but these are often impossible—one could not test improvements in puppy rearing, for example, or most training program changes. This is true of many things in humans as well; for this reason, experiments with identical twins are highly efficient (in the Lanarkshire milk experiment, a sample of n > 10,000 children could have been replaced with n~300). Identical twins are remarkably powerful even in the absence of randomization for inferring causation (2014) and by controlling for all genetics (which in human research, debunks a large fraction of all correlational research in psychology/sociology), make correlational analyses much more likely to deliver useful causal insights. As dog identical twins hardly exist, this has hitherto been entirely unavailable a research design for dog researchers, but clones change that.

-

Reduced Variance For Process Control: given the choice between a small group of clones and a much larger group of regular dogs, such that they have ostensibly identical average costs & the same number of expected successes, which should a breeder or trainer prefer? The small group of clones, of course.

The large group will, by the law of small numbers, have larger absolute fluctuations due to randomness, especially with a base rate like 1%. It’ll be ‘feast or famine’. Sometimes there will be considerably more, sometimes considerably less in absolute numbers. This will complicate planning greatly, stress facilities/trainers, risk delivering too few (or too many) dogs each year, and so on. Switching to clones with a higher base rate will make the overall process more controllable and predictable, and this is worth something.

-

-

use in selective breeding:

The major use of cloning in cattle is for accelerating breeding programs, and not for their immediate marginal increase in meat or milk yield. While dog breeding is not nearly as sophisticated, the benefits of cloning may also be larger for the long-term improvement in the breed than for its immediate benefits in each cloned dog:

-

clones can improve Estimates Of Genetic Merit by providing the most accurate possible heritability estimates (genetically identical individuals reared in different environments), and correcting individual estimates of traits, which is vital for planning any kind of breeding or selection program

-

a clone can have a Greater Genetic Potential than the average SF dog if intensive selection is done among SF dogs: if the best SF dog is selected for cloning, it’ll have a higher genetic potential than the default calculation of a truncated normal+regression toward the mean on a random SF dog would imply.

-

elite clones can be Heavily Used In Breeding Programs in allowing particular individuals to keep contributing genetically long after the original has become infertile or died, or contribute far more (as mentioned before, female dogs are highly limited in reproductive fecundity compared to males, but they could be cloned & born via surrogacy). For example, the first cloned dog, Snuppy, died in 2015, but is survived by 3 clones of himself.2, and the record for number of clones appears to be the 49 clones of the world’s tiniest dog, Miracle Milly.4

-

-

Value of Information: dog cloning may or may not be worthwhile, but if it is, the total returns from cloning hundreds of dogs per year indefinitely (plus the additional benefits) could be large. It would be valuable to know if it would work.

Since I have not found any SF/military-specific heritabilities reported in the scientific literature (and the SF dog programs generally seem genetically unsophisticated so there may not be any private or classified ones either), the only way to know is to try it out experimentally. The clones’ realized performance would also provide additional valuable information as it would estimate heritability, which would be useful for the regular kinds of breeding & selection as well—because they give an idea of how much one can predict a dog’s performance based on known relatives, and how fast a breeding program can/should proceed.

And since, to be profitable, the success rate of clones need to be >=9% (which is highly likely, see later), this is reasonably easy to estimate: a sample of ~50 clones would give a reasonably precise estimate as to the success rate and enable better decision-making as to whether to keep pursuing cloning (in which case more information will come in and firm up the decision) or drop it as a dead end due to too high costs and/or low heritability. (By the same logic, one could treat choice of donor itself as a multi-armed bandit problem to optimize the selection, since with success rates likely >50%, the necessary sample sizes will be not unreasonable and will be reached as clone use ramps up—like in South Korea, which has at least 42 clone dogs deployed in 2019 and appear to be increasing clone use as they claim great increases in success rates, decreases in costs, and net savings, implying substantial heritability.)

Modeling the SF Selection Problem

South Korea

How could we estimate the benefit of cloning? Given an active dog cloning program like Sooam and sufficient experience, it can be estimated directly.

et al 2014 reports that normally-bred detector dogs have a training success rate of 30% vs 86% for cloned dogs; the 30% appears to be based on the drug detection program, and the 86% is based on their sample of 7 of which 6 passed (ie. 6⁄7 = 0.86)5 et al 2018 notes as a followup

…the Toppy [clones] had the exact same genetic information as the elite drug sniffing dog, whereas the control dogs were the offspring of sniffer dogs. Surprisingly, all seven Toppy were selected with high scores, in contrast with the control group, of which three of the seven trained dogs were selected (Choi et al 201411ya). In the 6 months after the seven Toppy clones were added to airport security, the drug detection rate increased sixfold, at the same time saving the budget for selecting elite dogs. Thus, outstanding abilities can be passed on to the next generation by cloning identical dogs that inherit identical genetic material.

A 2017 Korea Bizwire provides a partial cost-benefit analysis in a press release:

Cloning and deployment of special forces dogs began in 201213ya as part of an initiative by the Rural Development Administration (RDA), in an effort to slash spending on police dog training. Special forces dogs come at a high price. For every dog, an estimated 1.3 billion won ($149,398.74$112,5542017) is spent on training them for multiple purposes such as human rescue, explosive detection and custom service. Despite the price, only 3 out of 10 dogs [30%] make it through the exhaustive training process to serve on police forces. Clone dogs, on the other hand, have a much higher pass rate of 80%, bringing down the training costs to 46 million won ($52,795.41$39,7752017). Compared to regular dogs, they offer savings of 65%.

“Sharing a competent and well-trained dog is no longer impossible, thanks to cloning”, said Im Gi-soon, a chief animal biotechnologist at the National Institute of Animal Science (NIAS).

It’s unclear if this 80% estimate is merely re-reporting Choi et al 201411ya, but if training each costs (3 $43,802.61$33,0002017, so going from 30% to 80% success rate means the clones have a training cost which is 39775⁄112554 = 35% that of the regular dogs or $95,569.32$72,0002017. The costs here clearly exclude cloning, but as Viagen is able to offer consumer dog cloning at $66,367.58$50,0002017 and Sooam has the advantage of experience & much greater scale (in addition to any patriotic discounts), the SK police could be getting a substantially lower price. But if they pay the full $66,367.58$50,0002017 anyway, then they are still reducing the total cost to ((33000+50000) × 10) / 8 = 103,750, saving $11,686$8,8042017. And at the $19,910.28$15,0002017 which may be the Viagen marginal cost, they would save $69,757.64$52,5542017.

However, one might doubt these numbers or how applicable they are, and they appear to exclude the substantial cost of cloning, rendering the cost-benefit incomplete.

A 2019 newspaper article states:

According to the Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency, 42 of its 51 [82%] sniffer dogs were cloned from parent animals as of April, indicating such cloned detection dogs are already making important contributions to the country’s quarantine activities. The number of cloned dogs first outpaced their naturally born counterparts in 201411ya, the agency said. Of the active cloned dogs, 39 are currently deployed at Incheon International Airport, the country’s main gateway…While the average cost of raising one detection dog is over 100 million won (US$107,516.52$85,6002019), it is less than half that when utilising cloned puppies, they said.

The lower price here may refer to lower levels of selectivity: “detection dog” vs “training them for multiple purposes”. But the wording implies this refers to total costs, since it states “raising” rather than just “training”, which usually means a total cost from the beginning. So if training each candidate dog costs the implied $32,254.96$25,6802019 and the success rates continue to be 30% vs 80%, and the clones have a per-success cost half that of normal dogs, then the implied amortized cloning cost would appear to be ~$10,751.65$8,5602019 (85,600 × 0.5 = (10 × (25,680+8,560)) / 8).

Cost-Benefit in Selection Problems

How would we approach this problem from first principles?

A SF dog is highly selected among candidate dogs, and it is either an acceptable SF dog or not. Being a SF dog requires a package of traits, ranging from physical health to courage to finely-controlled aggression (attacking if the handler orders, immediately stopping when counter-ordered), which sum up to an overall quality: somewhat poorer health can be made up by better smelling skills, say.

So a natural approach is to treat it as a logistic model, or more specifically, a liability threshold model (“Ch25, Threshold Characters”, Lynch & Walsh 199827ya): if a bunch of random variables all sum up to a certain high score, the dog becomes SF, otherwise, it is a normal dog. These random variables can be split into genetic variables, and everything else, ‘environmental’ variables.

Then the benefit of cloning can be estimated based on how much the genetic variables contribute to a high score, how high the genetic variables of a cloned SF dog might be (remembering that they are highly selected and thus imply regression to the mean), and this provides an estimate for increased probability that the clones will achieve a high score too. This is effectively an extreme case of truncation selection where a single individual is used as the ‘parent’ of the ‘next generation’. (This is not a bivariate maximum, because the clone is different from the selected donor individual, and is a draw from a new distribution distributed around the donor’s genetic potential.)

Once the probability a clone will succeed versus a random candidate dog is calculated, then one can get the cost of screening candidate dogs for a SF dog versus cloning+screening clone dogs for a SF dog.

So we need to know:

-

how difficult it is for a regular SF dog candidate to succeed, and what the implied threshold for a ‘SF score’ is of a random SF dog, and of an elite SF dog

-

if possible, how much less difficult it is for a cloned SF dog candidate to succeed, for the implied boost in their average scores

-

-

the cost of training a regular SF dog candidate

-

the cost of cloning an elite SF dog

-

the heritability of SF success, or failing that, dog traits in general as a prior

The answers seem to be:

-

<1% of breeder puppies may eventually make it to successful SF deployment; most selection happens in the 2 years before handover from the breeder to the military, and failure rates are substantially lower during the military training. For more conventional military or police use, success rates are much higher, and from puppy to deployment, probably more something like 25%.

Of successful SF dogs, the SF cloning pilots appear to be choosing from dogs in the top 1% or higher of SF dogs.

-

the post-handover cost of training per SF dog is likely >$62,801.7$50,0002019, with total lifetime cost being higher; conventional military/police dogs are again much less stringently selected/trained and thus cost much less, perhaps as low as $25,120.68$20,0002019.

-

dog cloning costs have dropped steeply since the first cloned dog in 20056 (in large part thanks to consumer demand for pet cloning), with 2019 list prices at <$62,801.7$50,0002019 and marginal costs possibly as low as $20,096.55$16,0002019 (so cloning at scale could cost only >$20,096.55$16,0002019)

Base Rates

Dog Success Rates

1990, in a broad review of military working dog training: “However, this ‘European solution’ turned out to be only temporary, as rejection rates continued to remain high, and continue today in the range of 25 to 50% (Andersen, Burke, Craig, Hayter, McCathern, Parks, Thorton).”7

Hammerstrom 200520ya, discussing Vietnam-era war dogs, cites Lemish 199629ya that there was “a high rejection rate of 30 to 50% of the potential canine recruits”.

et al 2010 finds in their US Air Force sample, 21% of dogs failed both types of training, summarizes the overall failure rate as “In many selection and training programs for police and detection dogs, more than half of the candidate dogs are rejected for behavioral reasons (Wilsson and Sundgren, 199728yab; Slabbert and Odendaal, 199926ya; et al 2007)”8, and notes that given the costs of a failed candidate, “While the improvements in prediction observed here were small (2–7%), given the costs of purchasing, importing, housing, and training (approximately $28,758.84$18,5002010US per dog), this small percentage improvement results in a substantial potential savings.”

A 2011 article on the 341st estimates that “The suitability rate runs around 50%. In other words, to produce 100 serviceable dogs per year, the program will attempt to train about 200.”

The 201411ya Bloomberg quotes Badertscher as saying “you’re lucky if one or two dogs out of a litter of eight might have the drive and focus to become the kind of dogs who can find bombs, take fire, and work independently on command—let alone jump out of airplanes at night.” A followup article quotes a trainer as estimating “maybe out of a litter of eight only four would be police service dogs or military dogs”.

Ritland 201312ya describes dogs appropriate for Navy Seals as being “a one-in-a-thousand (or more) proposition…I call them 1 percenters…but they are more like one in ten thousand.”9

Stripes, reporting on Sooam, states in 2016:

But breeding and training programs are costly and often inefficient. For example, the school that trains K-9s for the Department of Defense has found that the suitability rate runs around 50%, so the program tries to train about 200 dogs per year to produce 100 that are serviceable.

The aforementioned South Korean newspaper article put regular dogs in the sniffer training program at 30% success rates.

A trainer at the USDA National Detector Dog Training Center in 2019 described screening the general population of dogs for candidates: “We could look at 100 dogs and not come back with any…once they go through initial testing, the percentage of those dogs that make it is maybe 70%.”

Clone Success Rates

One of the first working dogs cloned was a particularly famous Canadian police dog Trakr, whose handler/owner James Symington, won a Sooam contest and received 5 clones of Trakr in 200916ya, which he began training in search-and-rescue under the auspices of his Team Trakr Foundation (TTF). TTF appears to have gone defunct sometime before 2014, with its last nonprofit filing in 201114ya, and I am unable to find any information about how the 5 clones worked out. (I have pinged TTF’s contacts.)

South Korean police in 201114ya reported a 7⁄7 success rate for the clones vs 3⁄10 for normal dogs.

Australia was reported to be working on a 201114ya deal to have up to 10 cloned sniffer dogs by 2013, but as there is no trace of these Australian dogs elsewhere, the deal must have fallen through.

The 201411ya Bloomberg article on Sooam (“For $100,000, You Can Clone Your Dog: These two were made to order in a South Korean lab. They’re only the beginning”) reported that Sooam had a contract for 40 dogs for South Korean clones of which “several are already in service” (presumably the 7 reported before), and also on the birth of 2 clones of a particularly elite SF dog then serving in Afghanistan (name classified), “Ghost” and “Echo”, later joined by a third, “Specter”; the American trainer involved, Brannon, praises the results, reporting in 2016 a 3⁄3 success rate (as opposed to a more typical 4⁄8 estimate given in the article):

Brannon says cloning seems to take the guess work out of normal breeding procedures. “Meaning, you have an excellent male an excellent female, and maybe out of a litter of eight only four would be police service dogs or military dogs,” according to Brannon. Specter is the third clone that the kennel has trained, and the other two are now working with federal SWAT units. “Right now we are 3 for 3 and they’re all successful,” said Brannon.

A New Scientist report in 2016 visiting Sooam mentions 4 German Shepherds from 1 donor for SK police: “two 9-month-old German shepherds, cloned for the national police. Their original was a working dog deemed particularly capable and well-disposed…Further down is another pair of puppies cloned from the same donor; these ones are just 2 months old.”, commenting on how “incredibly eerie” it is to see dogs with the same “mannerisms” and “perky left ear…like looking at a living growth chart.” If formal police training began at 2 years of age, by 2019 all 4 should be known as successes or failures.

Stripes reported in 2016 that 2 of Brannon’s clones finished training & were working for ATF and that Brannon was receiving another clone.10

3 Sooam-cloned Malinois were gifted to Russia in 2016; they reportedly badly failed initial testing in 2017, which was blamed on their thin fur coats being unsuited to the Yakutsk cold. (I don’t know if this should be considered a 0⁄3 example or not, given that there were apparently extenuating circumstances.)

The aforementioned South Korean newspaper article put clone dogs in the sniffer training program at 80% (vs 30%).

The first (and as of August 2019, only?) Chinese cloned police dog, Kunxun, was reportedly successful in training & accepted for duty. Another 6 dog clones began police training in November 2019.

As of late 2019, K9 dog clone success rates are apparently high enough to allow one K9 dog breeder to offer “a better, a five-year warranty instead of a single-year warranty, which is offered by the other kennel”; and an ex-Navy Seal trying to launch a business for providing guard dogs in large volume for schools to guard against mass shootings, Joshua Morton, trains only clones (a team of dog & handler is $157,004.26$125,0002019/year), due to the reliability of cloning & training a particular dog: “Cloning allows me to be consistent. Now, I know that I can tell a client, ‘Hey, I’ll have this dog ready in nine months.’…It’s way more effective, way more efficient.” Olof Olsson of Sooam in January 2021 is quoted as saying “80–90% end up going into service and we’ve been told multiple times that our clones respond better to training.” In 2021, Shaun Spelliscy cloned an unique sniffer dog trained to detect sulfuric metal ores, and thus far both cloned puppies appear to have the same talent as the original.

Reliable dog therapeutics. On a side note, one can wonder about medical sniffer dogs. Individual dogs have been demonstrated to be able to smell everything from C. difficile bacterial infections to breast cancer to Parkinson’s disease (as can at least one human), but as commenters typically point out, the individuality makes it difficult to fit medical sniffer dogs into medical regulatory frameworks—when each dog is an unique individual, how do you screen dogs for sniffer talent, train a standardized sniffer dog, or validate trained sniffers en masse (as we expect of medical drugs or tests)? Cloning could potentially drastically simplify the process of researching medical sniffer dogs, training them, procuring them in adequate quantities, and validating them. Given a clone of a known highly-talented sniffer dog put through a standardized training process, a regulatory standard could treat a trained clone as a kind of generic drug which satisfied bioequivalence, as opposed to if it were an entirely new dog (which are perhaps analogous to biosimilar drugs).

Heritability

The connection between being a clone and success probability is mediated by the accuracy of prediction from a donor to the clone, and to what extent a high donor ‘score’ predicts a high clone score.

A donor & clone are equivalent to a pair of identical twins raised apart (MZAs), and this prediction is simply the heritability of the trait (which is the square, so a r = 0.10 is a h2=0.01). In humans, h2s for everything average ~0.50 or r = 0.70; dogs seem to average lower heritabilities, with much of the genetic variance between dogs being the breed-level differences (which have already been exploited by dog breeders/SF trainers in their focus on Malinois etc), but even if the heritability is a fifth the size, a h2=0.10/r = 0.31 is useful.

SF-specific dog heritabilities should be calculable using existing pedigree records from breeders or the occasional government programs, but I didn’t find any mentioned in my reading.

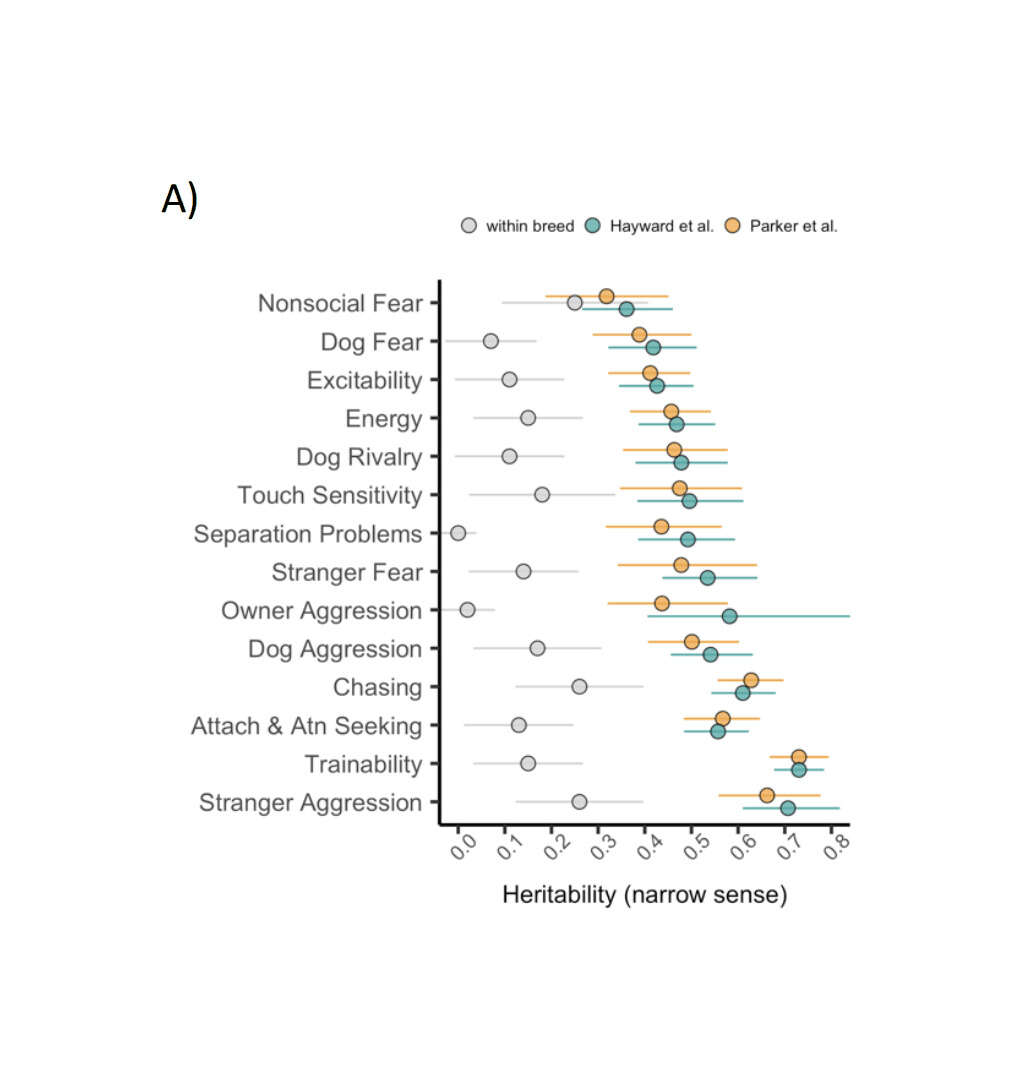

Dog heritabilities in general vary widely and are difficult to summarize because of equally widely varying methods, breeds, and analyses. Having been heavily selectively bred, there are large between-breed differences in behavior due to genetics (most recently: “Highly Heritable and Functionally Relevant Breed Differences in Dog Behavior”, Mac et al 201911; “Absolute brain size predicts dog breed differences in executive function”, et al 2019); these group-level heritabilities are irrelevant to this analysis as candidate dogs are already drawn from the best-suited breeds, and it is the remaining within-breed individual genetic differences which matters. This narrower heritability is most frequently estimated <0.50 on measured traits, and the most recent meta-analysis,2015 finds global mean heritabilities like 0.15/0.10/0.15/0.09/0.12, which would seem to not bode well for cloning.

However, the dog heritability literature is plagued with serious measurement error issues: the measured variables are unstable, unreliable, do not predict within the same dog over long periods of time, and are generally psychometrically inadequate. Measurement error biases heritability estimates towards zero: if a measurement of ‘temperament’ is not measuring temperament but something like how aggressive a particular trainer is, then regardless of how heritable temperament truly is, the measurement’s heritability will be near-zero; but one would be badly mistaken to then infer that temperament cannot be affected by breeding or that a clone will have a completely different temperament from the donor. In the papers which report relevant aspects of measurement error, the measurements are typically extremely bad, with r = 0.1–0.2 being common (for comparison, a properly administered IQ test will be r > 0.8). If one adjusts a measured heritability estimate like 0.09 for such noisy measurements, the true heritability could be easily be 0.66 or higher. Mac et al 2019 reports a set of behavioral trait heritabilities within-breed averaging ~0.15 (see also Table 4, et al 2017), using the C-BARQ inventory, developed with factor analysis and which has reasonable test-retest reliability r~0.5 and loading ~57% on the latent factors, suggesting a true mean heritability >0.24.

Another issue is the interpretation of a low heritability on individual behavioral traits: should SF heritability be thought of as a single trait, perhaps the sum of a large number of more atomic behavioral traits, in which case low heritabilities mean that an elite SF dog still has only a somewhat higher total genetic advantage than a random SF candidate dog? Or should, given the need for long sequences of correct decisions & actions drawing on many traits without a single mistake, we see it as more of a leaky pipeline/log-normal-like trait, in which a small advantage on each atomic behavioral trait (due to stringent selection + low heritabilities) nevertheless multiplies out to a large difference in the final outcomes—and so a clone will outperform much more than one would expect from a low heritability on each atomic trait?12 Perhaps most relevantly, 1982 examine guide dogs, and estimate the heritability of a ‘success’ trait rather than individual traits or subtests, which is much higher than the behavioral mean heritabilities: 0.44 (higher than 4⁄5 of the behavioral traits they estimate). A “success” trait here is an “index score”, by weighting correlated variables according to their importance, tend to be optimal predictors with much greater heritability, and to outperform individual variables (2018: ch37 “Theory of Index Selection”/ch38 “Applications of Index Selection”).

Sooam has published behavioral research on cloned dogs: et al 2018/ et al 2018/ et al 2018 reviews. None of the Sooam papers take a behavioral genetics approach or attempt to estimate heritability/genetic correlations/liability threshold models despite those being necessary for a correct answer, so they have to be read closely.

et al 2014 has already been reviewed. et al 2018 states that 4 clones of a cancer-sniffing dog were made but “ownership problems” prevented more than one from being evaluated, which et al 2018 states had similar capabilities as the donor (cited to et al 2015 which I am unable to download or read). et al 2016 compared 2 clone puppies, finding them similar on the Puppy Aptitude Test. et al 2016 tested learning/memory/exploration in 6 clones versus 4 controls, showing generally lower variance; no variance statistics are reported (just p-values), but counting dots on the plots, the implied variance all look >50% to me. et al 2016 mated a cloned detector dog with a regular female dog and tested the 10 offspring; the offspring achieved above average scores with a pass rate of 60% (which is roughly intermediate regular dogs and cloned dogs, suggesting high heritability given a non-detector mother). et al 2017/201813 found greater consistency of behavioral traits in clone than control puppies but did not estimate direct correlations/heritabilities, instead using calculating F-tests comparing the two groups’ variances; since these are unrelated control dogs and a single group of clone, the reduction in variance should be equivalent to heritability and can be read off from the F subscripts, in which case the various heritabilities are 0.20/0.35/0.40/0.23 etc.

Since clones have already been deployed in practice, we can try to work backwards from observed success rates of clones vs normal dogs. The anecdotal instances imply high success rates, nearing 100%, vs standard success rates of <50%, but a tiny total sample size and unclear definitions of success. More specifically, the South Korean sniffer program reportedly has 30% vs 80% on a common outcome, and the sample size is unclear but potentially into the hundreds.14

Using the liability threshold model, one could work back from a threshold and difference in success rates to estimate an implied heritability. In this case, the cutpoints for 30% and 80% are −0.52SD and +0.84SD, implying the clones are +1.36SD above the normals, ignoring any selection before enrollment. That is the mean they regressed back to, based on the unknown heritability (how much back to regress) and a certain threshold (how high the donor/original started off).

The lower the threshold, the greater heritability must be to avoid throwing away ability and still matching the observed success rate; the higher the threshold, the lower heritability can be while still providing enough ability-enrichment in the clones to have that higher success rate. In this case, we can assume a threshold like <1%, given that only elites are being cloned and this is consistent with everything else, in which case then the necessary heritability turns out to be… ~50%, which is plausible:

qnorm(0.80) - qnorm(0.30)

# [1] 1.36602175

0.513 * truncNormMean(qnorm(1-0.01))

# [1] 1.3672549So based on the existing dog literature and extrapolating from the current observed 80–100% dog success rates, a heritability of ~50% seems most plausible to me.

Costs

Training

But that may be worthwhile depending on how expensive it is to train enough dogs to get a successful dog, and how expensive cloning is.

For comparison, similar highly-trained civilian dogs, trained in Schutzhund (sometimes by trainers who used to train for Special Forces), can sell for $61,141.87$40,0002011–$91,712.8$60,0002011 with Ritland selling his dogs at $66,367.58$50,0002017–$132,735.17$100,0002017, and the best award-winning “executive protection dogs” selling for up to $351,565.73$230,0002011. Bloomberg notes “Canines with finely trained noses now fetch $33,183.79$25,0002017 and up on the open market, where border patrol units, the State Department, and private security firms go for canine talent.”

2005 quotes two cost estimates of a US military contractor BSI 1969–197055ya at $45,813.54$10,0001974 (Lemish 199629ya/199926ya, War Dogs: A History of Loyalty and Heroism) and $68,720.32$15,0001974 (cited to “Perry Money, a former Marines Corps handler of a BSI dog”), and mentions a program to breed dogs for better health & “superior ambush detection” (which failed for unknown reasons); he also quotes US Air Force LTC Bannister, commander of the 341st Training Squadron, as estimating the 120-day “DoD MWD Course” at $83,576.98$50,0002005 “per trained dog” (unclear if this refers to average over all dogs, or per successful ‘trained’ dog)15. et al 2010 quotes US Air Force training of patrol & detection dogs at ~$28,758.84$18,5002010, with a 21% total failure rate implying a 1.2x higher cost per success of ~$36,402.47$23,4172010. A 201114ya NYT article on Marines notes it is “an expensively trained canine (the cost to the American military can be as high as $61,141.87$40,0002011 per dog)”. Ritland & Brozek 201312ya quotes a US Navy SEAL dog’s individual cost at >$73,893.88$50,0002013.16 South Korean police quote a drug sniffer dog at $61,141.87$40,0002011 for training in 201114ya. 2017 reports “The U.S. military spends up to $375,640.53$283,0002017 to train a working war dog…Once it has a promising pup, the Pentagon spends an additional $55,748.77$42,0002017 to train a K9 unit…When all is said and done, a fully trained military dog costs about as much as a small missile.”17 A 2019 Chinese source on the first domestically-cloned police dog (cloned from a donor police dog who is “one in a thousand”) cites a standard police dog training cost of $94,202.56$75,0002019 over 5 years; the clone was reportedly successful in training. A 2019 Wired notes “Highly trained bomb- and disease-sniffing dogs are in short supply and expensive, as much as $31,400.85$25,0002019 per pooch.”

These estimates vary considerably, and seem to reflect heterogeneity in what cost is being calculated, how selective a role or facility is due to difficulty of role (police dogs cost less than single-role military dogs who cost less than multi-role dogs who cost less than Special Forces dogs). But it’s hard to see what is driving some of these differences, like the 6x difference between Ritland/Bannister and Bloomberg’s estimate, as a Navy SEAL dog is presumably a “working war dog”. It seems to me that the Ritland/Bannister figure is referring to the cost to train a single dog who happened to be successful (plausible since Bannister is providing a 200520ya estimate from the dog training facilities he oversees), while the latter refers to the total cost to get one successful dog out of an unspecified number of candidates; if they are referring to the same dogs, then the implied success rate is 1⁄6. Ritland guesstimates that the failure rate among his SF dogs, after they have passed all of the thresholds which lead to formal acquisition by the US Navy (which Ritland emphasizes represents most of the selection done on the dogs), is “more like 3 or 4 in 10 instead of 7.5 out of 10”, which, combined with some additional failures or expenses elsewhere in the process, seems reasonably consistent: if each dog costs >$73,893.88$50,0002013, then even at face-value that failure estimate implies substantially higher price-tags. Alternately, the Bloomberg estimate might be a ‘total lifetime cost’ estimate of some sort, including all of the maintenance and equipment and costs during deployment and retirement, while Ritland/Bannister is referring only to the upfront training cost.

It is worth noting, given how much selection takes place before sale to SF trainers, that these costs embed the cost of failure beforehand: breeders are not charities, so however much it costs on net to raise, train, and test the dogs which don’t get bought for training, the sale price of a candidate SF dog must cover the washouts as well (after recouping whatever is possible by washouts’ alternate uses, perhaps in less selective roles), or else the breeder would go out of business.

Cloning

Dog cloning, on the other hand, cost $141,362.82$100,0002015 list price in 2015 from Sooam, down from the original $229,688.16$150,0002008 in 200817ya, when Bernann McKinney received 5 cloned pit bulls from Sooam.18 Viagen in 2018 reportedly offers a $64,685.75$50,0002018 plan; the profiled pet owner, Amy Vangemert, received 3 cloned puppies (one of which was adopted out) and incidentally intends to do it again as necessary. (Viagen’s price remained the same in 2019.) The Chinese firm Sinogene, which cloned a police dog in 2019, reportedly charges $66,569.81$53,0002019–$70,337.91$56,0002019 for a dog clone, and claims to have done >40 total as of September 2019. A November 2019 anecdote involving a billionaire’s cloned dog stopping a drone mentions “Mini Vader, the $180,868.91$144,0002019 (£111,563) pup that Alki David sourced from Dr Olof Olsson’s Korean-based cloning lab SwissX, earned his jaw-dropping price tag with a mid-air rescue that unfortunately left his owner with a nastily-gashed hand.” Sooam apparently offers a guarantee, and Viagen will refund if not successful, so that price should be firm. (Why Sooam is able to charge twice as much as Viagen, or why SwissX—better known for marijuana-related activities—costs 2–3× as much as anyone else, I do not know.) By 2022, Sinogene was offering dog cloning as low as $25,000.

For comparison, the other kind of commercially-offered pet cloning is for cats. The first commercial cat clone, Little Nicky reportedly cost $86,752.9$50,0002004 in 200421ya; more recently, cat clones from Viagen cost $47,711.66$35,0002016 in 2016 and $31,400.85$25,0002019 in 2019 (although the article notes that “Cloning a dog costs $62,801.7$50,0002019 while a cat is now $43,961.19$35,0002019—the company recently increased the fee by $12,560.34$10,0002019 to cover rising costs.”). I have also been told privately by someone who cloned their cat with Viagen in 2018 that it cost them ~$19,405.73$15,0002018. Overseas, the first Chinese cat clone from Sinogene Biotechnology Company in July 2019 as the start of a commercial service quotes Sinogene as saying it “is expected to cost 250,000 yuan ($44,463.61$35,4002019) each. Zhao told the Global Times that several cat owners had already booked the service, hinting that the future market could be huge. The company also offers a dog cloning service, costing 380,000 yuan [$68,328.25$54,4002019].” After scaling to 100 cats, their 2022 cat price had dropped to $17,500.

The real price per dog may be lower. Their practice seems to be to engage in overkill by implanting multiple clone embryos to ensure the minimum specified number of healthy clones, and offer all resulting healthy live-births to the customer—for example, Vangemert is not mentioned as being charged $150k instead of $50k for the 3 puppies, as would be the case if Viagen charged $50k for each success and she requested 2 and got 3. So the per-clone cost appears to have become surprisingly reasonable: $50k–$100k for 1 dog, and potentially <$16k (if a purchase results in 3 puppies as in Vangemert’s case), suggesting that the price has a large fixed cost to it and the marginal costs might be quite small, which is not helpful in the pet-replacement scenario but would be important to large-scale cloning of specific animals like elite drug sniffers. For comparison, cattle and horse cloning have become industrialized at ~$10–15k; dog cloning is apparently more difficult (harder to control estrous, Viagen notes), so that may be a lower bound for the foreseeable future.

Liability Threshold Model

This requires us to estimate two things: the threshold and the heritability on the liability scale.

For common police dogs and other working dogs, training appears to be not that hard, and estimates of 30–50% are seen. This gives a threshold of 50%, or in standard deviations, 0SD.

A SF dog is much more selective, and the only specific estimate given is <1% by Mike Ritland, which in standard deviations, means each dog would be >=2.33SD, and the actual mean created by this selection effect is +2.66SD. (If this is confusing imagine a threshold like 50%: is the mean of everyone over 50% equal to 50%? No, it has to be higher, and the mean of everyone >=0SD/>=50% is actually more like 0.8SD/75%—not 0SD/50%!—and we need to use the truncated normal distribution to get it right.)

The clone of the SF dog shares only genetics with it, it doesn’t benefit from the unique luck and environment that the original did which helped it achieve it success, so it will regress to the mean. If genetics determined 100% of the outcome, then the clones would always be +2.66SD just like the donor, and hence make the 1%/+2.33SD cutoff 100% of the time, as they have the same genetic potential and zero environmental input (although that is extremely unlikely a scenario, due to measurement error in the testing if nothing else). While if genetics contributed 0% to the outcome and did not matter, then the clones will make the 1% cutoff just as often as if they were a random dog sampled from their breeders ie. 1%. And in between, in between.

Under a more plausible case like genetics determining 50% of the variability (a common level of heritability for better-studied human traits), then that is equivalent to a perfect genetic predictor correlating r = 0.7; the r, remember, is equivalent to ‘for each 1 SD increase in the independent variable, expect +r SDs in the dependent variable’, so since the clone donor is +2.66SD, the clones will only be 2.66 × 0.7 = 1.86 SD above the mean. If the clones are distributed around a mean of +1.86SD thanks to their genes, what’s the probability they will then reach up to a total of +2.33SD (the threshold) with help from the environment & luck? Half the variance is used up, and the environment has to contribute another 2.33 − 1.86 = +0.47SD, despite causing differences of only 0.7SD on average. In that case, the clones will have ~26% chance of being successful—which is a remarkable 26x greater than a random dog, but also far from guaranteed.

But one can do better, since it is not necessary to select a random SF dog (with their implied average of +2.66SD) but one can select the best SF dog and clone this elite specimen instead. Multi-stage selection is always more efficient than single-stage selection, particularly when we are interested in extremes/tails, due to the ‘thin tails’ of the normal distribution. At any time there are thousands of SF dogs worldwide, and more in retirement (and perhaps more if tissue samples have been preserved from earlier generations), so the gain from an additional selection step is potentially large (especially when we consider tail effects), and since only 1 dog is necessary for cloning, why settle for anything less than the best? If one can select at least the best SF dog out of 100019, then the new ‘threshold’ is +4.26SD and the expectation for our elite dog is +4.47SD, and likewise, the clones at 50% heritability would be +3.16SD, which is considerably above the original SF threshold of 2.33SD, and now fully 88% of the clones would be expected to succeed at SF training. (An implication here is that with enough screening, and perhaps tracking off clone success rates to refine estimates of genetic potential, success rates approaching 100% are entirely possible—one simply needs a donor so far off the charts genetically that the remaining 30% variance rarely pushes clones under the fixed threshold; these failures corresponding to extreme situations like rare crippling diseases or infections, abuse, accidents, etc.)

Source code defining the truncated normal distribution, the cloning process, and a Monte Carlo implementation20:

## exact mean for the truncated normal distribution:

truncNormMean <- function(a, mu=0, sigma=1, b=Inf) {

phi <- dnorm

erf <- function(x) 2 * pnorm(x * sqrt(2)) - 1

Phi <- function(x) { 0.5 * (1 + erf(x/sqrt(2))) }

Z <- function(beta, alpha) { Phi(beta) - Phi(alpha) }

alpha = (a-mu)/sigma; beta = (b-mu)/sigma

return( (phi(alpha) - phi(beta)) / Z(beta, alpha) ) }

## If we select the top percentile, the cutoff is +2.32SD, but the mean is higher, +2.66SD:

qnorm(0.99)

# [1] 2.32634787

truncNormMean(qnorm(0.99))

# [1] 2.66521422

truncNormMean(qnorm(1-0.01^2))

# [1] 3.95847967

cloningBoost <- function(successP=0.01, preThreshold=0.01, heritability=0.5,

verbose=FALSE) {

threshold <- qnorm(1-preThreshold)

successThreshold <- qnorm(1-successP)

originalMean <- truncNormMean(threshold)

cloneMean <- 0 + (sqrt(heritability) * originalMean) ## regress to mean

regression <- originalMean - cloneMean

cloneP <- pnorm(cloneMean - successThreshold, sd=sqrt(1-heritability))

if (verbose) { print(round(digits=3, c(threshold, successThreshold, originalMean,

cloneMean, regression, cloneP))) }

return(cloneP) }

## Alternative Monte Carlo implementation to check:

cloningBoostMC <- function(successP=0.01, preThreshold=0.01, heritability=0.5,

verbose=FALSE, iters1=10000000, iters2=1000) {

threshold <- qnorm(1-preThreshold)

successThreshold <- qnorm(1-successP)

r <- sqrt( heritability)

r_env <- sqrt(1-heritability)

## NOTE: this is a brute-force approach chosen for simplicity. If runtime is

## a concern, one can sample from the extremes directly using the beta-transform trick:

## https://gwern.net/order-statistic#sampling-gompertz-distribution-extremes

population <- rnorm(iters1, mean=0, sd=1)

eliteDonors <- population[population>=threshold]

clones <- as.vector(sapply(eliteDonors, function(d) {

rnorm(iters2, ## sample _n_ clones per donor

## regress back to mean for true genetic mean:

mean=d*r,

## left-over non-genetic variance affecting clones:

sd=r_env) }))

successes <- clones>=successThreshold

cloneP <- mean(successes)

if (verbose) { library(skimr)

print(skim(population)); print(skim(eliteDonors)); print(skim(successes)) }

return(cloneP)

}

## Varying heritabilities, 0-1:

cloningBoost(successP=0.01, heritability=1.0, verbose=TRUE)

# [1] 2.326 2.326 2.665 2.665 0.000 1.000

# [1] 1

cloningBoost(successP=0.01, heritability=0.8, verbose=TRUE)

# [1] 2.326 2.326 2.665 2.384 0.281 0.551

# [1] 0.551145688

cloningBoost(successP=0.01, heritability=0.5, verbose=TRUE)

# [1] 2.326 2.326 2.665 1.885 0.781 0.266

# [1] 0.266071352

cloningBoost(successP=0.01, heritability=0.2, verbose=TRUE)

# [1] 2.326 2.326 2.665 1.192 1.473 0.102

# [1] 0.102340263

cloningBoost(successP=0.01, heritability=0.0, verbose=TRUE)

# [1] 2.326 2.326 2.665 0.000 2.665 0.010

# [1] 0.01

## Enriched selection by selecting elites rather than random:

cloningBoost(successP=0.01, preThreshold=0.01 * (1/1000), heritability=0.5, verbose=TRUE)

# [1] 4.265 2.326 4.479 3.167 1.312 0.883

# [1] 0.882736927

## Probability of surpassing the original: while it decreases with increasing threshold…

## (see also https://gwern.net/order-statistic#probability-of-bivariate-maximum )

round(digits=3,

unlist(Map(function(threshold) {

cloningBoost(successP=pnorm(threshold), preThreshold=pnorm(threshold), heritability=0.5) },

seq(0,-8, by=-0.5))))

# [1] 0.788 0.668 0.544 0.428 0.324 0.238 0.169 0.115 0.076 0.048 0.030 0.018

# 0.010 0.005 0.003 0.001 0.001

#

## …it is still *far* above base-rates:

round(digits=0,

unlist(Map(function(threshold) {

cloningBoost(successP=pnorm(threshold), preThreshold=pnorm(threshold), heritability=0.5) / pnorm(threshold) },

seq(0,-8, by=-0.5))))

# [1] 2 2 3 6 14 38

# 125 496 2405 14273 103765

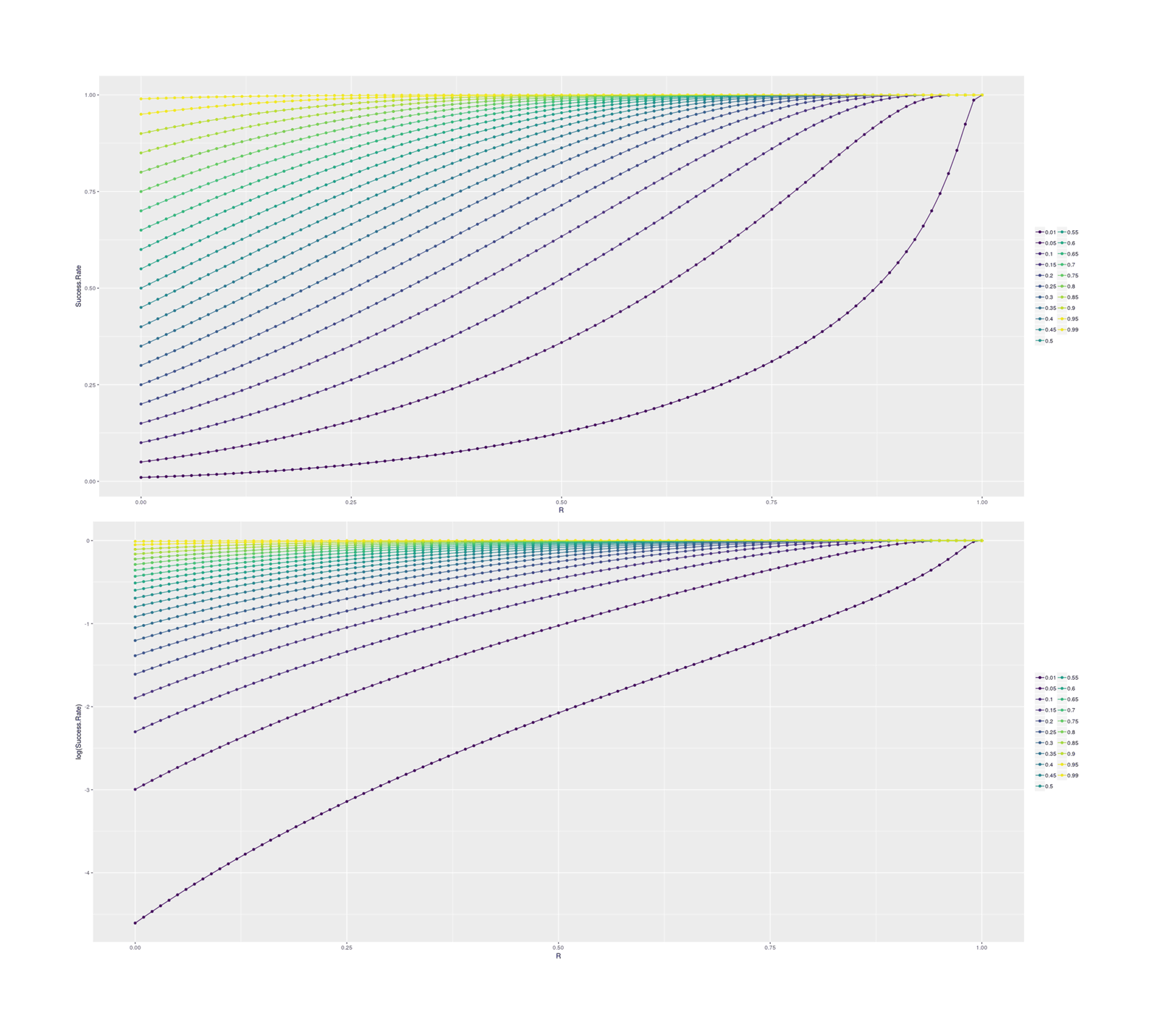

# [12] 925193 10123773 136019115 2244775378 45505318504 1148533117232For insight, we can look at how final success probability increases with different heritabilities/rs, in the single-step selection scenario (corresponding to a random selection of SF dogs for cloning) and for the double-step selection (selecting a top 1% SF dog for cloning):

## Plotting the increase in subsequent probability given various correlations:

df1 <- data.frame(PriorP=numeric(), R=numeric(), Success.Rate=numeric())

for (p in c(0.01, seq(0.05, 0.95, by=0.05), 0.99)) {

for (r in seq(0,1, by=0.01)) {

df1 <- rbind(df1, data.frame(PriorP=p, R=r,

Success.Rate=cloningBoost(successP=p, heritability=r^2)))

}

}

library(ggplot2); library(gridExtra)

p1 <- qplot(R, Success.Rate, color=as.ordered(PriorP), data=df1) +

geom_line() + theme(legend.title=element_blank())

p2 <- qplot(R, log(Success.Rate), color=as.ordered(PriorP), data=df1) +

geom_line() + theme(legend.title=element_blank())

grid.arrange(p1, p2, ncol=1)

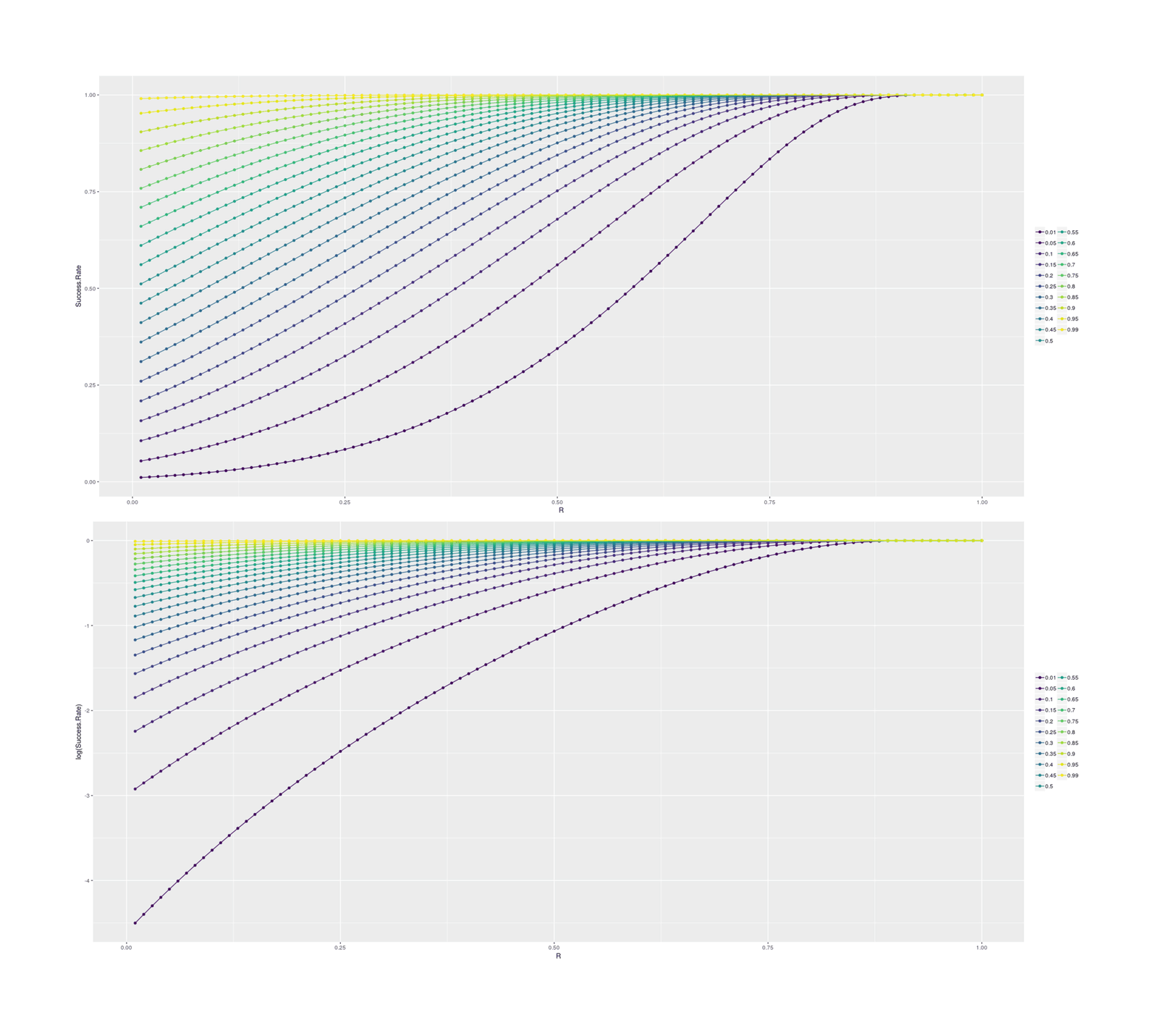

## Double-step selection:

df2 <- data.frame(PriorP=numeric(), R=numeric(), Success.Rate=numeric())

for (p in c(0.01, seq(0.05, 0.95, by=0.05), 0.99)) {

for (r in seq(0.01,1, by=0.01)) {

df2 <- rbind(df2, data.frame(PriorP=p, preThreshold=p * 0.01, R=r,

Success.Rate=cloningBoost(successP=p, preThreshold=p * 0.01, heritability=r^2)))

}

}

library(ggplot2); library(gridExtra)

p1 <- qplot(R, Success.Rate, color=as.ordered(PriorP), data=df2) +

geom_line() + theme(legend.title=element_blank())

p2 <- qplot(R, log(Success.Rate), color=as.ordered(PriorP), data=df2) +

geom_line() + theme(legend.title=element_blank())

grid.arrange(p1, p2, ncol=1)

How the probability of post-selection success increases given a prior base rate and a predictor of r power for single-step selection; absolute probabilities, and log-transformed.

Likewise, but with an additional selection step prior to cloning to further select the best one.

Cost-Benefit

Does cloning minimize loss? My cost-benefit below takes the cost per final dog without cloning, computes the implied per-dog-candidate cost, and then computes the increased success rate for a given threshold+heritability, and sees if the expected cloning+training cost is less than the original total cost.

dogCloningCB <- function(successP, heritability, totalTrainingCost, marginalCloningCost, verbose=FALSE) {

normalLoss <- totalTrainingCost

marginalTrainingCost <- totalTrainingCost / (1/successP)

cloningP <- cloningBoost(successP=successP, heritability=heritability)

cloningLoss <- ((1/cloningP) * (marginalTrainingCost + marginalCloningCost))

if(verbose) {return(list(Boost=cloningP, Cost.normal=normalLoss, Cost.marginal=marginalTrainingCost, Cost.clone=cloningLoss,

Profitable=normalLoss>cloningLoss, Profit=normalLoss-cloningLoss)) }

return(normalLoss-cloningLoss) }

## Example: 30% success rate, 50% heritability, $85k per-dog training cost, $15k per-clone cost

dogCloningCB(0.30, 0.5, 85600, 15000, verbose=TRUE)

# $Boost

# [1] 0.972797623

#

# $Cost.normal

# [1] 85600

#

# $Cost.marginal

# [1] 25680

#

# $Cost.clone

# [1] 41817.5364

#

# $Profitable

# [1] TRUE

#

# $Profit

# [1] 43782.4636Scenarios

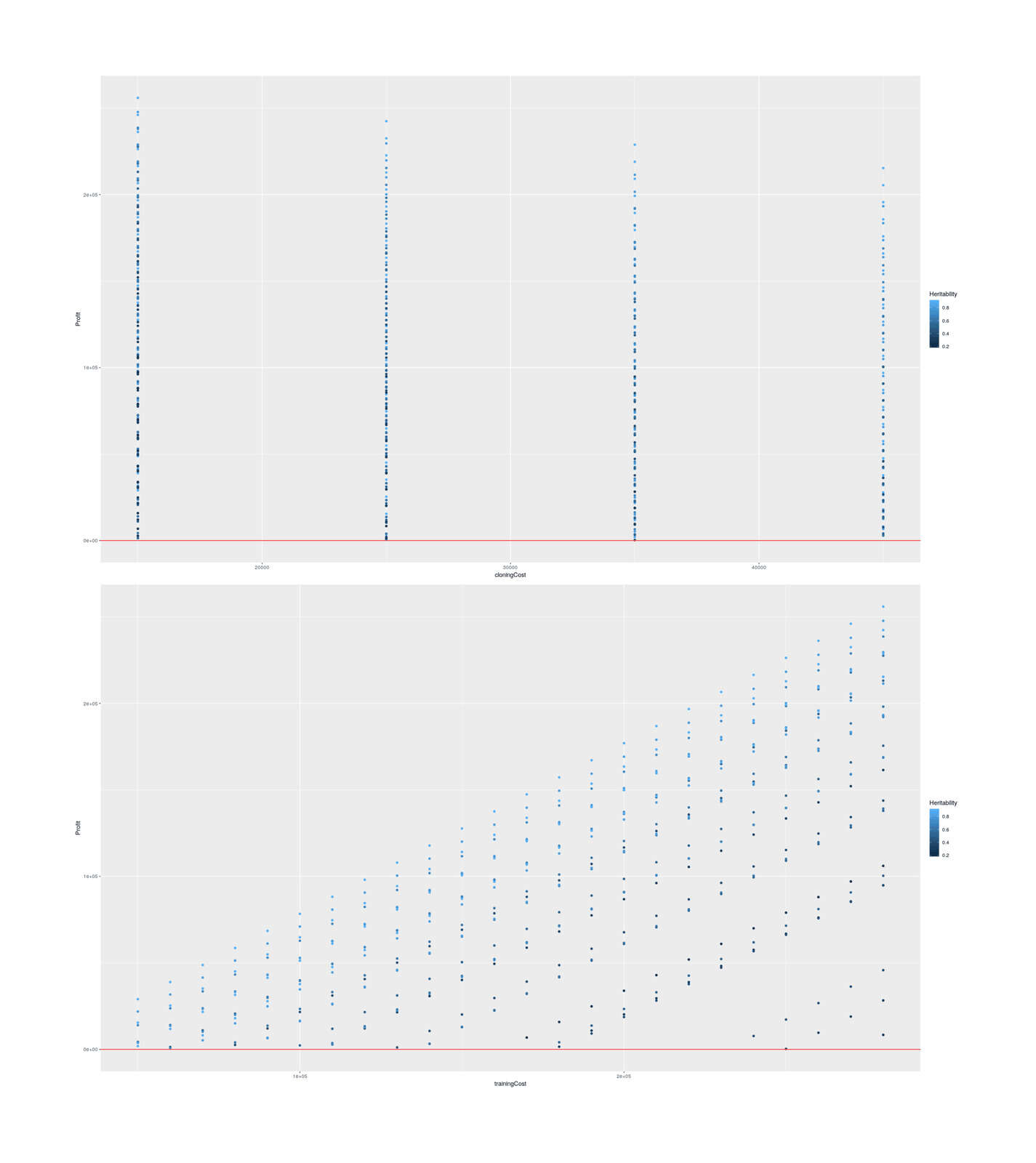

As the key heritability trait is almost completely unknown and heritabilities of dog behavioral traits are all over the map and seem to suffer from severe measurement error issues, we might as well consider a wide range of scenarios to get an idea of what it would take. For success/threshold, we continue with 1%; for heritability, we’ll consider the most plausible range, 0–90%; for training cost, we’ll do the full $50k–$283k range since while it’s unclear what these numbers mean, treating them as a total per-dog cost is being conservative and makes it harder for cloning to be profitable, and for cloning costs we’ll consider the Vangemert case up to Viagen’s list price of $50k (since there doesn’t seem to be any good reason to pay twice as much to Sooam).

scenarios <- expand.grid(SuccessP=0.01, Heritability=seq(0, 0.9, by=0.10), trainingCost=seq(50000, 283000, by=10000), cloningCost=seq(15000, 50000, by=10000))

scenarios$Profit <- round(unlist(Map(dogCloningCB, scenarios[,1], scenarios[,2], scenarios[,3], scenarios[,4])))

## Plot relationships among profitable scenarios:

scenariosProfitable <- scenarios[scenarios$Profit>0,]

library(ggplot2); library(gridExtra)

p1 <- qplot(cloningCost, Profit, color=Heritability, data=scenariosProfitable) + geom_hline(yintercept=0, color="red")

p2 <- qplot(trainingCost, Profit, color=Heritability, data=scenariosProfitable) + geom_hline(yintercept=0, color="red")

grid.arrange(p1, p2, ncol=1)

## All profitable scenarios:

scenariosProfitable

# ...

The SF dog cloning scenarios showing profit vs possible cloning & training costs, colored by heritabilities.

|

Success Probability |

Heritability |

Training cost |

Cloning Cost |

Profit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

50000 |

15000 |

4333 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

50000 |

15000 |

13962 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

50000 |

15000 |

21877 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

50000 |

15000 |

29015 |

|

0.01 |

0.5 |

60000 |

15000 |

1369 |

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

60000 |

15000 |

14038 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

60000 |

15000 |

23729 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

60000 |

15000 |

31695 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

60000 |

15000 |

38879 |

|

0.01 |

0.5 |

70000 |

15000 |

10993 |

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

70000 |

15000 |

23743 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

70000 |

15000 |

33497 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

70000 |

15000 |

41514 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

70000 |

15000 |

48744 |

|

0.01 |

0.4 |

80000 |

15000 |

2576 |

|

0.01 |

0.5 |

80000 |

15000 |

20617 |

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

80000 |

15000 |

33449 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

80000 |

15000 |

43264 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

80000 |

15000 |

51332 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

80000 |

15000 |

58609 |

|

0.01 |

0.4 |

90000 |

15000 |

12086 |

|

0.01 |

0.5 |

90000 |

15000 |

30242 |

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

90000 |

15000 |

43154 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

90000 |

15000 |

53032 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

90000 |

15000 |

61151 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

90000 |

15000 |

68473 |

|

0.01 |

0.4 |

100000 |

15000 |

21596 |

|

0.01 |

0.5 |

100000 |

15000 |

39866 |

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

100000 |

15000 |

52859 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

100000 |

15000 |

62799 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

100000 |

15000 |

70970 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

100000 |

15000 |

78338 |

|

0.01 |

0.3 |

110000 |

15000 |

2785 |

|

0.01 |

0.4 |

110000 |

15000 |

31106 |

|

0.01 |

0.5 |

110000 |

15000 |

49490 |

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

110000 |

15000 |

62565 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

110000 |

15000 |

72567 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

110000 |

15000 |

80788 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

110000 |

15000 |

88202 |

|

0.01 |

0.3 |

120000 |

15000 |

12119 |

|

0.01 |

0.4 |

120000 |

15000 |

40616 |

|

0.01 |

0.5 |

120000 |

15000 |

59114 |

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

120000 |

15000 |

72270 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

120000 |

15000 |

82334 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

120000 |

15000 |

90607 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

120000 |

15000 |

98067 |

|

0.01 |

0.3 |

130000 |

15000 |

21453 |

|

0.01 |

0.4 |

130000 |

15000 |

50126 |

|

0.01 |

0.5 |

130000 |

15000 |

68738 |

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

130000 |

15000 |

81976 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

130000 |

15000 |

92102 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

130000 |

15000 |

100425 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

130000 |

15000 |

107932 |

|

0.01 |

0.3 |

140000 |

15000 |

30787 |

|

0.01 |

0.4 |

140000 |

15000 |

59636 |

|

0.01 |

0.5 |

140000 |

15000 |

78362 |

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

140000 |

15000 |

91681 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

140000 |

15000 |

101869 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

140000 |

15000 |

110244 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

140000 |

15000 |

117796 |

|

0.01 |

0.3 |

150000 |

15000 |

40121 |

|

0.01 |

0.4 |

150000 |

15000 |

69146 |

|

0.01 |

0.5 |

150000 |

15000 |

87987 |

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

150000 |

15000 |

101386 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

150000 |

15000 |

111637 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

150000 |

15000 |

120062 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

150000 |

15000 |

127661 |

|

0.01 |

0.3 |

160000 |

15000 |

49455 |

|

0.01 |

0.4 |

160000 |

15000 |

78656 |

|

0.01 |

0.5 |

160000 |

15000 |

97611 |

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

160000 |

15000 |

111092 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

160000 |

15000 |

121404 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

160000 |

15000 |

129881 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

160000 |

15000 |

137526 |

|

0.01 |

0.2 |

170000 |

15000 |

6819 |

|

0.01 |

0.3 |

170000 |

15000 |

58789 |

|

0.01 |

0.4 |

170000 |

15000 |

88166 |

|

0.01 |

0.5 |

170000 |

15000 |

107235 |

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

170000 |

15000 |

120797 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

170000 |

15000 |

131171 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

170000 |

15000 |

139699 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

170000 |

15000 |

147390 |

|

0.01 |

0.2 |

180000 |

15000 |

15842 |

|

0.01 |

0.3 |

180000 |

15000 |

68123 |

|

0.01 |

0.4 |

180000 |

15000 |

97676 |

|

0.01 |

0.5 |

180000 |

15000 |

116859 |

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

180000 |

15000 |

130502 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

180000 |

15000 |

140939 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

180000 |

15000 |

149518 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

180000 |

15000 |

157255 |

|

0.01 |

0.2 |

190000 |

15000 |

24865 |

|

0.01 |

0.3 |

190000 |

15000 |

77457 |

|

0.01 |

0.4 |

190000 |

15000 |

107186 |

|

0.01 |

0.5 |

190000 |

15000 |

126483 |

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

190000 |

15000 |

140208 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

190000 |

15000 |

150706 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

190000 |

15000 |

159337 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

190000 |

15000 |

167119 |

|

0.01 |

0.2 |

200000 |

15000 |

33887 |

|

0.01 |

0.3 |

200000 |

15000 |

86791 |

|

0.01 |

0.4 |

200000 |

15000 |

116696 |

|

0.01 |

0.5 |

200000 |

15000 |

136107 |

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

200000 |

15000 |

149913 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

200000 |

15000 |

160474 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

200000 |

15000 |

169155 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

200000 |

15000 |

176984 |

|

0.01 |

0.2 |

210000 |

15000 |

42910 |

|

0.01 |

0.3 |

210000 |

15000 |

96125 |

|

0.01 |

0.4 |

210000 |

15000 |

126206 |

|

0.01 |

0.5 |

210000 |

15000 |

145732 |

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

210000 |

15000 |

159619 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

210000 |

15000 |

170241 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

210000 |

15000 |

178974 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

210000 |

15000 |

186849 |

|

0.01 |

0.2 |

220000 |

15000 |

51933 |

|

0.01 |

0.3 |

220000 |

15000 |

105459 |

|

0.01 |

0.4 |

220000 |

15000 |

135716 |

|

0.01 |

0.5 |

220000 |

15000 |

155356 |

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

220000 |

15000 |

169324 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

220000 |

15000 |

180009 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

220000 |

15000 |

188792 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

220000 |

15000 |

196713 |

|

0.01 |

0.2 |

230000 |

15000 |

60956 |

|

0.01 |

0.3 |

230000 |

15000 |

114794 |

|

0.01 |

0.4 |

230000 |

15000 |

145226 |

|

0.01 |

0.5 |

230000 |

15000 |

164980 |

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

230000 |

15000 |

179029 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

230000 |

15000 |

189776 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

230000 |

15000 |

198611 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

230000 |

15000 |

206578 |

|

0.01 |

0.2 |

240000 |

15000 |

69979 |

|

0.01 |

0.3 |

240000 |

15000 |

124128 |

|

0.01 |

0.4 |

240000 |

15000 |

154736 |

|

0.01 |

0.5 |

240000 |

15000 |

174604 |

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

240000 |

15000 |

188735 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

240000 |

15000 |

199544 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

240000 |

15000 |

208429 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

240000 |

15000 |

216442 |

|

0.01 |

0.2 |

250000 |

15000 |

79002 |

|

0.01 |

0.3 |

250000 |

15000 |

133462 |

|

0.01 |

0.4 |

250000 |

15000 |

164246 |

|

0.01 |

0.5 |

250000 |

15000 |

184228 |

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

250000 |

15000 |

198440 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

250000 |

15000 |

209311 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

250000 |

15000 |

218248 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

250000 |

15000 |

226307 |

|

0.01 |

0.2 |

260000 |

15000 |

88025 |

|

0.01 |

0.3 |

260000 |

15000 |

142796 |

|

0.01 |

0.4 |

260000 |

15000 |

173756 |

|

0.01 |

0.5 |

260000 |

15000 |

193852 |

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

260000 |

15000 |

208145 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

260000 |

15000 |

219079 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

260000 |

15000 |

228067 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

260000 |

15000 |

236172 |

|

0.01 |

0.2 |

270000 |

15000 |

97048 |

|

0.01 |

0.3 |

270000 |

15000 |

152130 |

|

0.01 |

0.4 |

270000 |

15000 |

183266 |

|

0.01 |

0.5 |

270000 |

15000 |

203476 |

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

270000 |

15000 |

217851 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

270000 |

15000 |

228846 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

270000 |

15000 |

237885 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

270000 |

15000 |

246036 |

|

0.01 |

0.2 |

280000 |

15000 |

106070 |

|

0.01 |

0.3 |

280000 |

15000 |

161464 |

|

0.01 |

0.4 |

280000 |

15000 |

192776 |

|

0.01 |

0.5 |

280000 |

15000 |

213101 |

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

280000 |

15000 |

227556 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

280000 |

15000 |

238614 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

280000 |

15000 |

247704 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

280000 |

15000 |

255901 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

50000 |

25000 |

3733 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

50000 |

25000 |

15476 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

60000 |

25000 |

478 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

60000 |

25000 |

13551 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

60000 |

25000 |

25341 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

70000 |

25000 |

10246 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

70000 |

25000 |

23370 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

70000 |

25000 |

35205 |

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

80000 |

25000 |

3986 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

80000 |

25000 |

20013 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

80000 |

25000 |

33188 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

80000 |

25000 |

45070 |

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

90000 |

25000 |

13691 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

90000 |

25000 |

29781 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

90000 |

25000 |

43007 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

90000 |

25000 |

54934 |

|

0.01 |

0.5 |

100000 |

25000 |

2282 |

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

100000 |

25000 |

23397 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

100000 |

25000 |

39548 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

100000 |

25000 |

52826 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

100000 |

25000 |

64799 |

|

0.01 |

0.5 |

110000 |

25000 |

11906 |

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

110000 |

25000 |

33102 |

|

0.01 |

0.7 |

110000 |

25000 |

49316 |

|

0.01 |

0.8 |

110000 |

25000 |

62644 |

|

0.01 |

0.9 |

110000 |

25000 |

74664 |

|

0.01 |

0.5 |

120000 |

25000 |

21530 |

|

0.01 |

0.6 |

120000 |

25000 |