The Exquisitely English (and Amazingly Lucrative) World of London Clerks

It’s a Dickensian profession that can still pay upwards of $650,000 per year.

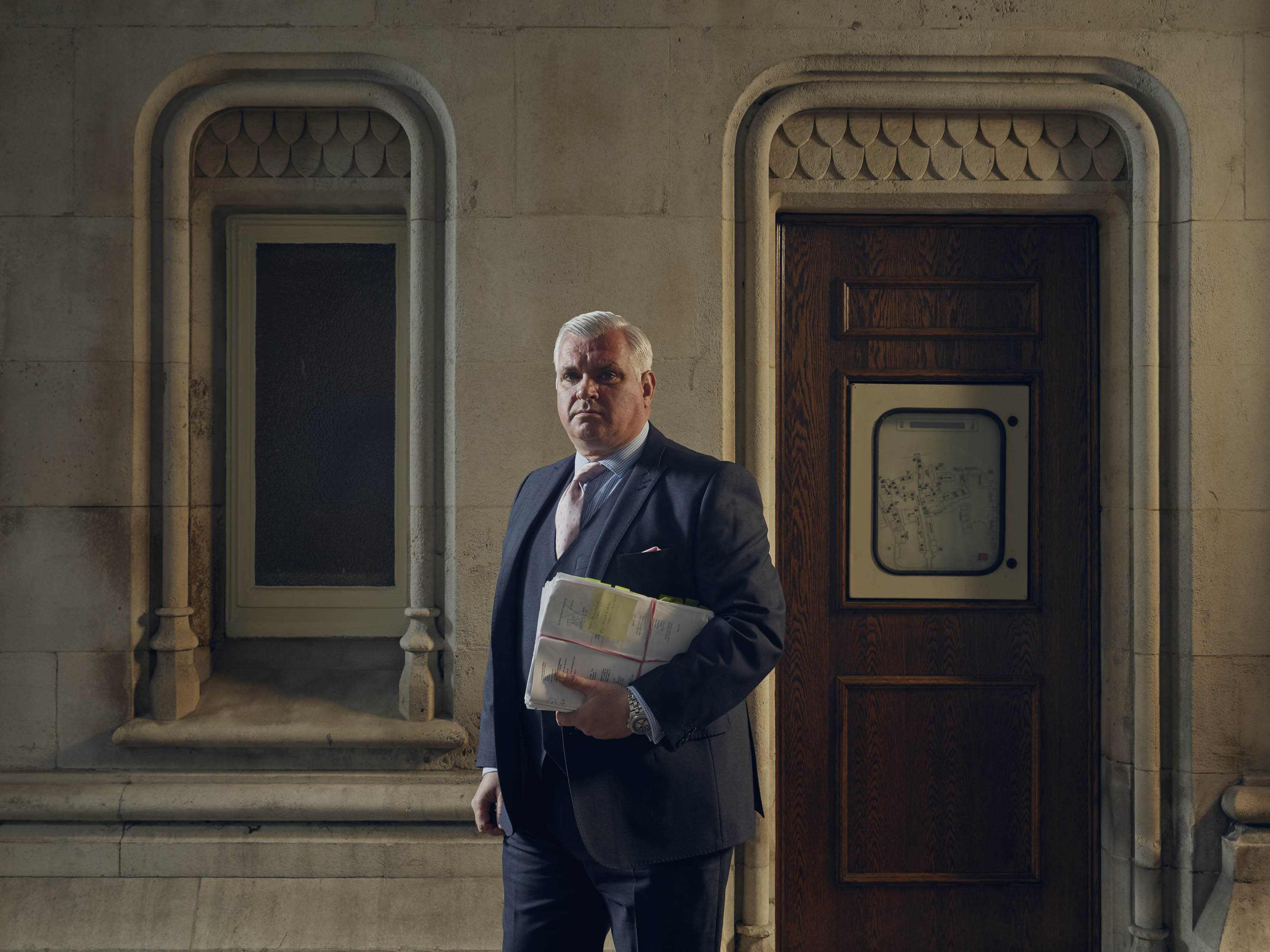

Alex Taylor of Fountain Court Chambers.

At Fountain Court Chambers in central London, the senior clerk is called Alex Taylor. A trim, bald 54-year-old who favors Italian suiting, Taylor isn’t actually named Alex. Traditionally in English law, should a newly hired clerk have the same Christian name as an existing member of the staff, he’s given a new one, allegedly to avoid confusion on the telephone. During his career, Taylor has been through no fewer than three names. His birth certificate reads “Mark.” When he first got to Fountain Court in 1979, the presence of another Mark saw him renamed John. Taylor remained a John through moves to two other chambers. Upon returning to Fountain Court, in 2008, he became Alex. At home his wife still calls him Mark.

Alex/John/Mark Taylor belongs to one of the last surviving professions of Dickensian London. Clerks have co-existed with chimney sweeps and gene splicers. It’s a trade that one can enter as a teenager, with no formal qualifications, and that’s astonishingly well-paid. A senior clerk can earn a half-million pounds per year, or more than $650,000, and some who are especially entrenched make far more.

Clerks—pronounced “clarks”—have no equivalent in the U.S. legal system, and have nothing in common with the Ivy League–trained Supreme Court aides of the same spelling. They exist because in England and Wales, to simplify a bit, the role of lawyer is divided in two: There are solicitors, who provide legal advice from their offices, and there are barristers, who argue in court. Barristers get the majority of their business via solicitors, and clerks act as the crucial middlemen between the tribes—they work for and sell the services of their barristers, steering inquiring solicitors to the right man or woman.

Clerks are by their own cheerful admission “wheeler-dealers,” what Americans might call hustlers. They take a certain pride in managing the careers of their bosses, the barristers—a breed that often combines academic brilliance with emotional fragility. Many barristers regard clerks as their pimps. Some, particularly at the junior end of the profession, live in terror of clerks. The power dynamic is baroque and deeply English, with a naked class divide seen in few other places on the planet. Barristers employ clerks, but a bad relationship can strangle their supply of cases. In his 1861 novel Orley Farm, Anthony Trollope described a barrister’s clerk as a man who “looked down from a considerable altitude on some men who from their professional rank might have been considered as his superiors.”

Fountain Court is among the most prestigious groups in London practicing commercial law, the branch that deals with business disputes. One day last summer, Taylor gave a tour of the premises, just north of the River Thames. The waiting room had been recently remodeled, with upholstered sofas, low tables, and asymmetrically hung pictures that called to mind an upmarket hotel. Taylor explained that the barristers had tried to walk an aesthetic line between modernity and the heritage that clients expect of people who are sometimes still required to wear a horsehair wig to court. Barristers are self-employed; chambers are a traditional way for them to band together to share expenses, though not profits. The highest-ranking members, barristers who’ve achieved the rank of Queen’s Counsel, are nicknamed silks, after the plush material used to make their robes. But even the silks cannot practice without the services of clerks, who operate from a designated room in each chambers, matching the ability and availability of barristers to solicitors in need.

In the Fountain Court clerks room, Taylor sat at the head of a long table, flanked by subordinates wearing telephone headsets. Clerking has historically been a dynastic profession monopolized by white working-class families from the East End of London; Taylor’s son is a clerk. Predominantly, clerks hail from Hertfordshire, Kent, and above all Essex, a county that’s ubiquitously compared to New Jersey in the U.S. Many clerks rooms in London remain male-dominated, but several women work for Taylor, including two team leaders.

Each morning, a platoon of Taylor’s junior clerks sets forth into London pushing special German-manufactured two-wheeled trolleys, equipped with chunky tires for navigating the city’s streets and stairs. They’re laden with hundreds of pounds of legal documents that must be delivered to Fountain Court barristers at various courtrooms, from the nearby Royal Courts of Justice to the Supreme Court, more than a mile away. Hard physical labor doesn’t really correspond to the more senior work of clerking, which is phone- and email-based, and trolley-pushing is often pointed to as a reason for the relative dearth of female clerks higher up the career ladder. One junior Fountain Court clerk, Amber Field, 19, described how on one occasion, when she took hold of a trolley’s handlebars and tried to muscle it into a rolling position, it didn’t budge—she lifted herself up instead, like a gymnast on the parallel bars.

But the idea that time “on the trolleys” is necessary persists. British commercial courtrooms have been slow to adopt technology; barristers at Fountain Court and elsewhere remain adamant that they can only advocate properly with stacks of paper on hand, rather than off a screen. Some clerks argue that the trolleys help juniors absorb skills, learn the city’s legal sites, and meet important people. But additionally, the trolley work serves as an unglamorous rite of passage, guarding the gilded summit of clerking from interlopers. Trolleys keep a closed shop closed, well into the 21st century. In the era of Brexit, as Britons turn inward, few professions better embody their abiding interest in keeping things as they are.

London’s barrister population is getting more diverse, but it’s still disproportionately made up of men who attended the best private secondary schools, and then Oxford and Cambridge, before joining one of four legal associations, known as Inns of Court—a cosseted progression known as moving “quad to quad to quad.” In short, barristers tend to be posh. Being a successful clerk, therefore, allows working-class men and, increasingly, women to exert power over their social superiors. It’s an enduring example of a classic British phenomenon: professional interaction across a chasmic class divide.

One of the most peculiar aspects of the clerk-barrister relationship is that clerks handle money negotiations with clients. Barristers argue that avoiding fee discussions keeps their own interactions with clients clean and uncomplicated, but as a consequence, they’re sometimes unaware of how much they actually charge. The practice also insulates and coddles them. Clerks become enablers of all sorts of curious, and in some cases self-destructive, behavior.

At Fountain Court, I spent an afternoon with Paul Gott, one of the chambers’ star barristers. He stood surrounded by packing cases—he was in the process of moving his office from an annex across the street, where it had become a small tourist attraction. Visitors would stop outside to stare through a window at Gott’s extraordinary collection of objects: antique barristers’ wig tins, an original wax-cylinder Dictaphone, a deactivated Kalashnikov assault rifle and hand grenades, stamps, and an assortment of vintage medical instruments of alarming purpose.

Like many top barristers, Gott had effectively won the English educational system: He has a double-first-class degree (top marks in preliminary as well as final exams) from Cambridge. As he spoke about his work—Gott specializes in securing injunctions against striking workers—he cut open a packing case with a metal device that he identified as a fleam, an obsolete surgical implement used for bloodletting. Outside of work, Gott divides his time between two homes: one in a Martello tower—a kind of defensive fort built to fend off Napoleon—and another in a converted military landing craft moored on the Thames that he calls the “Houseboat Potemkin.” The Chambers and Partners legal directory describes Gott as “phenomenally intelligent,” but his eccentric professional demeanor is only possible because he has a hardheaded Alex Taylor to intercede between him and the world, wrangling with clients and handling payments. Taylor creates the space for Gott’s personality even as he’s employed by him.

A more unsavory side of this coddling relationship is apparent elsewhere. At a chambers called 4 Stone Buildings, a clerk called Chris O’Brien, 28, told me he was once asked to dress a boil on a barrister’s back. Among clerks, tales of buying gifts for their barristers’ mistresses are legion. But they maintain a level of sympathy for their employers, whose work is competitive and often profoundly isolating. Clerks speak of how their masters, no matter how successful, live in perpetual fear that their current case will be their last. Counsel, the English bar’s monthly journal, recently ran a major spread on mental health. John Jones, a prominent silk at Doughty Street Chambers who’d represented Julian Assange, died last year when he jumped in front of a train.

John Flood, a legal sociologist who in 1983 published the only book-length study of barristers’ clerks, subtitled The Law’s Middlemen, uses an anthropological lens to explain the relationship. He suggests that barristers, as the de facto priests of English law—with special clothes and beautiful workplaces—require a separate tribe to keep the temple flames alight and press money from their congregation. Clerks keep barristers’ hands clean; in so doing they accrue power, and they’re paid accordingly.

I asked more than a dozen clerks and barristers, as well as a professional recruiter, what the field pays. Junior clerks, traditionally recruited straight after leaving school at 16 and potentially with no formal academic qualifications, start at £15,000 to £22,000 ($19,500 to $28,600); after 10 years they can make £85,000. Pay for senior clerks ranges from £120,000 to £500,000, and a distinct subset can earn £750,000. The Institute of Barristers’ Clerks disputed these figures, saying the lows were too low and the highs too high. But there’s no doubt that the best clerks are well-rewarded. David Grief, 63, a senior clerk at the esteemed Essex Court Chambers, spoke to me enthusiastically about his personal light airplane, a TB20 Trinidad.

Money is tightest in criminal law. One chambers, 3 Temple Gardens, lies 200 yards from Fountain Court but might as well inhabit a different dimension. Access is via a plunging staircase lined with green tiles similar to those in a Victorian prison. The clerks room, in the basement, is stacked with battered files detailing promising murders, rapes, and frauds. The senior clerk is Gary Brown, 53, who once played professional soccer. Even the barristers appear harried and ashen in comparison with their better-fed commercial-law counterparts.

The mean income of a criminal barrister working with legal-aid clients is £90,000, meaning even a successful criminal barrister likely makes less than a top commercial clerk. At Fountain Court, once described as a place so prestigious that “you could get silk just by sitting on the toilet,” I watched Taylor casually negotiate a fee above £20,000; at 3 Temple Gardens, the clerks wrangled deals for a few hundred pounds. The best-paid criminal clerks make perhaps £250,000 per year—and yet there’s an excitement and pressure to a criminal clerks room that’s absent in the commercial field.

One day I sat next to Brown’s deputy, Glenn Matthews, 41, as he worked out the running order for the courts the next day. For several sultry hours, Matthews juggled the availability of his barristers with the new cases coming in from solicitors and more that moved off a wait list. Some barristers only work as defense counsel, some only prosecute, and some alternate roles, depending on the case; Matthews balanced all this and also made elaborate plans to match barristers who’d already be in a certain provincial town with other cases nearby, to save on travel. It was complex, skilled work done with panache.

Many in the criminal field are motivated by a belief that they’re a crucial part of the British judicial machinery, and their work closely corresponds with the public’s imagination of what it is to work in the law. Silk, the preeminent British legal TV show of the past few years, focuses on a criminal chambers. It features a lupine senior clerk, Billy Lamb, who bullies, cajoles, bribes, and often appears to have the most fun.

As a chancery chambers, dealing with wills, trusts, banking, and other matters, 4 Stone Buildings is an establishment from the old school, with a facade still pockmarked by World War I bombs. Guests stride down a corridor with deep red wallpaper to a waiting room equipped with a fireplace and shelved with aged lawbooks. The best of the silks’ rooms face out across a low dry moat to the gardens of Lincoln’s Inn—one of the four Inns of Court, along with Gray’s Inn, Inner Temple, and Middle Temple, all less than a mile apart.

There are 34 barristers at 4 Stone, including Jonathan Crow, whose office features a stuffed crow on the mantelpiece. The clerks room is downstairs and furnished significantly less smartly, with desks set behind a shoplike wooden counter. When I visited, the clerks were exclusively white and male, and five of the six were from Essex. At the helm was David Goddard, 64, in charge since 1983. One legal handbook notes that his nickname is “God,” for his grip on the chambers.

I sat for two days in God’s room, observing clerks’ interactions with barristers across the wooden transom that were redolent of the upstairs-downstairs dynamic of Downton Abbey. The barristers spoke with “received pronunciation”—the polished accent traditionally spoken by the social elite and which, unlike lower-class accents, doesn’t vary by region; the clerks, fluent Essex—a nasal accent, with elements of cockney. One vital function clerks play is finessing a “cab rank” rule, set by the Bar Standards Board, that states a barrister must take the first case that comes, regardless of their interest. Clerks can invent or manipulate commitments to allow their barristers to turn down work that doesn’t appeal. (I didn’t witness this at 4 Stone.)

Before the U.K. decimalized its currency in 1971, clerks received “shillings on the guinea” for each case fee. Under the new money system, the senior clerks’ take was standardized at 10 percent of their chambers’ gross revenue. Sometimes, but not always, they paid their junior staff and expenses out of this tithe. Chambers at the time were typically small, four to six barristers strong, but in the 1980s, they grew. As they added barristers and collected more money, each chambers maintained just one chief clerk, whose income soared. The system was opaque: The self-employed barristers didn’t know what their peers within their own chambers were paid, and in a precomputer age, with all transactions recorded in a byzantine paper system, barristers sometimes didn’t know what their clerks earned, either. Jason Housden, a longtime clerk who now works at Matrix Chambers, told me that, when he started out in the 1980s at another office, his senior clerk routinely earned as much as the top barristers and on occasion was the best-paid man in the building.

One anecdote from around the same time, possibly apocryphal, is widely shared. At a chambers that had expanded and was bringing in more money, three silks decided their chief clerk’s compensation, at 10 percent, had gotten out of hand. They summoned him for a meeting and told him so. In a tactical response that highlights all the class baggage of the clerk-barrister relationship, as well as the acute British phobia of discussing money, the clerk surprised the barristers by agreeing with them. “I’m not going to take a penny more from you,” he concluded. The barristers, gobsmacked and paralyzed by manners, never raised the pay issue again, and the clerk remained on at 10 percent until retirement.

Since the 1980s, fee structures have often been renegotiated when a senior clerk retires. Purely commission-based arrangements are now rare—combinations of salary and incentive are the rule, though some holdouts remain. Goddard told me last summer that he receives 3 percent of the entire take of the barristers at 4 Stone; later he said this was inaccurate, and that his pay was determined by a “complicated formula.” (Pupil barristers, as trainees are known, start there at £65,000 per year, and the top silks each make several million pounds.)

The huge sums that clerks earn, at least relative to their formal qualifications, both sit at odds with the feudal nature of their employment and underpin it. In some chambers, clerks still refer to even junior barristers as “sir” or “miss.” Housden remembers discussing this issue early in his career with a senior clerk. He asked the man whether he found calling people half his age “sir” demeaning. The reply was straightforward: “For three-quarters of a million pounds per year, I’ll call anyone sir.”

Most chambers have become less formal, even as the class distinctions between barrister and clerk are in many ways intact. At 4 Stone, Goddard refers to the heads of chambers, John Brisby and George Bompas, as “Brizz” and “Bumps.” The traditional generic term used by clerks for a barrister is “guvnor,” though this appears to be fading. The intimacy of the long-term clerk-barrister relationship is nuanced. Goddard once walked into the room of a senior member of chambers who was proving particularly truculent. Goddard asked, “Why are you being such a c---?”

The barrister’s eyes lit up. “I love it when you talk to me like that,” he replied.

The origins of clerking, like much of English law, run to the medieval period. In the 14th century, a lawyer would employ an individual known as a “manciple” to look after his house, in return for “a bed and a reasonable dinner,” the legal historian Samuel Thorne once wrote. Clerks as we might recognize them today existed by the 1666 Great Fire of London and were firmly established by the Victorian era. Efforts to modernize the clerking system have flickered in recent decades, with some success and a lot of rancor.

Around 1989 a former peace activist named Christine Kings attended a dinner party in East London where a group of barristers were complaining about their clerks, who they said terrorized them, ran their lives, and also earned much more than they did. The barristers had an idea: to set up a new sort of practice unfettered by ancient quirks of the bar, including the power of those uppity middlemen. They asked Kings, who had no legal background, to join them, taking on many of the duties typically performed by a senior clerk, but for much reduced pay.

Doughty Street Chambers, as they named their new association, controversially set up its operations outside the footprint of the four Inns of Court. As an interloper, Kings wasn’t popular with clerks. When she was a few months into the job, standing at the top of Chancery Lane, one tried to spit in her face. As others began to take on similar roles at various chambers—ex-military men at first, who met with little success, and then women—Kings organized informal gatherings to promote solidarity. One attendee said she’d found rat poison in her desk drawer.

Kings became the first professional chief executive officer of a barristers’ chambers in London. At a mass meeting of some 300 barristers and other personnel in the early 1990s, she spoke about her new role and the ways it broke from traditional clerking. When someone asked what she was paid, she replied that the Bar Council suggested £44,000. The barristers gaped—it was a fraction of what they paid their chief clerks to run their establishments. Since then, several chambers have experimented with professional heads from nonclerking backgrounds, under titles ranging from CEO to director, with varying responsibilities. At Fountain Court, an administrator deals with logistics, while the core part of clerking—the routing of incoming cases to barristers and fee negotiations—remains in traditional hands. (Kings, 59, now works at Outer Temple Chambers.)

Doughty Street Chambers has thrived. It’s best known as the professional home of the accomplished human-rights lawyer Amal Clooney. Another outfit that eschews the more suffocating traditions of the English bar is Matrix Chambers, which sits in a former police station at the northern fringe of Gray’s Inn. Matrix emerged in 2000 when a group of mostly human-rights barristers, including Cherie Blair, the wife of then-Prime Minister Tony Blair, splintered off from seven other chambers. Together, they aimed for a funky, fresh aesthetic, installing a DayGlo-illuminated reception desk inherited from an ad agency and refusing to pose for the traditional portraits of staff standing in front of lawbooks. Those who resented such modernizations referred to Matrix as Ratmix.

Seventeen years after its founding, Matrix is an established part of the London legal landscape, with a particularly strong reputation in public, media, and employment law. (Matrix has represented Bloomberg LP, the owner of Bloomberg Businessweek.) Matrix doesn’t use the term “clerk.” Instead, there are three teams, called “practice managers,” that each deal with solicitors in different areas of the law. At the top is a chief executive, Lindsay Scott, a former solicitor who takes on many of the strategic duties of a senior clerk.

On a Friday morning, I watched as Hugh Southey, one of Matrix’s silks and a descendant of the Romantic poet Robert Southey, gave a presentation to the practice management team on “terrorism prevention and investigation measures.” The British government introduced these controversial legal maneuvers in 2011 to manage potential terrorists who can’t be charged or deported. Most chambers pay limited attention to the legal education of their clerks, who as a consequence sell a product they don’t understand. Matrix’s crew, with more women and nonwhite faces than most clerking staffs, are routinely given opportunities to learn.

Some in London legal circles regard Matrix’s reforms as semantic, noting the staff is thick with men from classic clerking backgrounds. Housden, Matrix’s practice director, started work as a teenage clerk, and one of his colleagues has been a clerk for 25 years. As different as Matrix or other reformers might want to be, they’re in the same marketplace as more orthodox chambers, and they play by a common set of rules and expectations that goes back centuries. One prevailing understanding of last year’s Brexit vote is that it signaled a desire to be more British, less beholden to outsiders’ notions of progress. Essex, the spiritual home of the clerk, had two of the five districts that voted the most overwhelmingly to leave the European Union.

As I spent time with London’s clerks, I had the impression of a group of people who’d learned some of the language of modernity, but weren’t themselves fully of the modern world—their boozy pub lunches attested to that. Some of the staff at Matrix have newfangled titles, it’s true. But as Taylor might observe, all that’s really changed is the name.